Last week I shared the history of the Battle of Spring Hill and the Battle of Franklin, as well as my visit to the battlefield at Spring Hill and the Rippavilla Mansion. If you haven’t read that, click here to do so. It’ll put today’s post in context because today is about my visit to the two historical sites in Franklin. Carter House was in the line of fire and the Carnton Mansion served as a hospital.

Volunteer Opportunity

I said last week that I loved hearing the story of the Battle of Franklin three times, the truth is I hadn’t actually planned on going to Rippavilla, Carter House and Carnton Plantation. The price for admission to both the Carter House and Carnton Plantation is $18 each. Since only separated by less than two miles. I decided I’d only visit Carnton Plantation.

But, as luck would have it, when I was doing my research, I looked under “Events” on the museum’s website, as I always do, and discovered something called Park Day at Carter House. One day a year, volunteers do projects around the property and in return the volunteers get a free pass.

My timing was perfect. A week before my visit, I drove to Carter House and spent five hours with a handful of Franklin community members clearing brush. At lunchtime, it was fun to sit around and hear everyone’s story.

Carter House

The tidbits that intrigued me at Carter House.

- When the battle began, members of the Carter household, including their slaves, and members of the Lotz family (their neighborhoods) took refuge in the cellar. As part of the tour, we went into the low-ceiling cellar. The largest of the three rooms had a circle of wooden chairs, each with the name of a person who spend the night in that cellar. They sat in the dark for fear the light of a candle would draw fire, the sound of war all around them. Eerie.

- A cannon ball left a round indentation in one of the porch walls. They had it covered by a screen so it wasn’t very photogenic. But it was neat.

- One of the Carter sons, Tod, fought in most of the Army of Tennessee’s battles. At one point captured by the Federal Army, he escaped to rejoin his group before the Atlanta and Tennessee campaigns. Then, he was mortally wounded 200 yards from his own house in the Battle of Franklin. The next day, his sister walking the battlefield found him still clinging to life. But he died in his family home on the day after, December 2, 1864.

- Outside the house is the smoke house. It was the last thing we saw on our tour. We stood around the closed front door. The tour guide, after 90 minutes of painting a picture of the Battle of Franklin for us, said, “This doesn’t need words.” Then he opened the door. The room was empty, expect for all the pinholes of light coming through all the bullet holes. It is believed to be the most-bullet ridden wooden structure still standing from the Civil War. It was a sobering, sad moment.

Carnton Plantation

Of the three, this was my favorite. If you are in the area and only have time for one, visit Carnton Plantation. The tour guide painted the most vivid picture. The Carnton Plantation stood between the two warring sides. He said, “Imagine a line of men marching (Hood’s men). When they come to Carnton the line opens to go around the house and closes on the other side.” It gave me chills imagining what it must’ve been like.

Of the three, this was my favorite. If you are in the area and only have time for one, visit Carnton Plantation. The tour guide painted the most vivid picture. The Carnton Plantation stood between the two warring sides. He said, “Imagine a line of men marching (Hood’s men). When they come to Carnton the line opens to go around the house and closes on the other side.” It gave me chills imagining what it must’ve been like.

At the same time, just like at Carter House, they got a knock on the door that their house was taken over. They were allowed to choose one room for the family but the rest would be use as a hospital for the men marching into battle. The family chose the attic.

Four (or maybe five) rooms were quickly converted into workable operating rooms. And then the wounded started coming. Fast and furious. By the hundreds. A staff officer wrote that “the wounded, in hundreds, were brought to [the house] during the battle, and all the night after. And when the noble old house could hold no more, the yard was appropriated…”

An old thick twisty tree outside the mansion. Imagine soldiers from the Battle of Franklin leaning against the old tree.

The guide said if a man had a wound between his neck and his bellybutton, they didn’t bother operating. Too much time for a person unlikely to make it. Those men lay in one of the rooms as they died, a process that sometimes took days. The sounds were excoriating. Men with limb wounds were operated on. Or, I should say, amputated.

The floors remain blood-stained. There was a story that the doctors tossed amputated limbs out of the windows. And the pile of body parts reached the second floor window. In fact, if you’d gone on the tour in the early days, you might have heard that story.

Over time, what we know about history can change. Letters from one of the doctors, later discovered, told the full story of the day. In them, he describes putting limbs in baskets, not throwing them out the window. And, the blood stain patterns confirm this. The surgeries took place under the windows because of light. But the windows stayed open for air ventilation because the chemical used to knock out soldiers could also knock out a doctor if he wasn’t careful. Baskets next to the surgery table filled with limbs quickly. When full, it was moved to the furthest corner and another was placed beside the table. Blood rings where baskets sat remain.

The last family member sold the mansion in 1911. It had a couple owners. It moved me to learn that the last private owner, a doctor himself, donated the mansion and 10 acres of land. He wanted the historical mansion preserved. However, he did so with one condition. The blood-stained floors stayed as is.

Carnton became the largest field hospital in the area. It was hard to visualize the number of men squeezed into the house. We were in one room and the tour guide told us 100 men laid. These were not large rooms. It was hard to imagine half as many laying on the floor.

It is fascinating to learn the owners of the house were expected to bear the cost associated with whatever it was used for. At Carnton, this meant they bore the cost of running a hospital for hundreds of wounded. Could you afford to have your house suddenly filled with wounded soldiers and be able to feed them for the entire time of their recuperation?

John and Carrie McGavock were multi-millionaires (in today’s dollars) before the start of the Civil War. At the end, they were in debt. And, like so many, their wealth and the plantation never recovered to what it was pre-war.

The last soldier left Carnton 18 months after the Battle of Franklin, a year after the war ended. In a funny twist, when he left, he took the nanny with him as his bride as they’d fallen in love during his recovery.

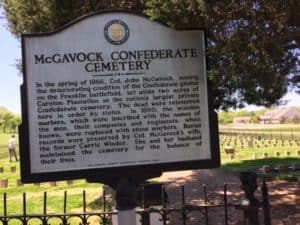

McGavock Confederate Cemetery

The stone markers at McGavock Confederate Cemetery. John and Carrie donated the land and maintained the graves for the whole of their lives, some 50 years after the end of the Civil War.

The Union soldiers who stayed behind after the battle buried the Union soldiers. They left the Confederate soldiers where they fell. Many men would never be identified. At some point later, other soldiers buried the Confederate dead around the Franklin Battlefield. A couple years later, John and Carrie noticed the deteriorating conditions of the graves on the Franklin Battlefield.

John and Carrie set aside two acres of their property next to their family cemetery and re-interred the Confederate soldiers. At their expense. It is the final resting place of nearly 1,500 Confederate soldiers. They identified as many as they could and for years afterward, family members would make pilgrimages to the cemetery to see if their lost soldier might be among the buried. They created records and maintained the cemetery for the remainder of their lives.

Just one path of many at the Carnton Plantation’s Garden. This one lead to a fountain in the center.

Outside the house is a beautiful garden. It reminds me of an English garden. You just don’t see big gardens with walking paths much today. I loved it. It made me think of two of my grandmothers since they were both gardeners and love flowers. I wished they were still alive because as soon as I saw it. I imagined writing each a long letter describing the garden.

The sights and sounds—and smells—from that day must’ve been something no one would ever forgot. How could you?

I certainly studied the Civil War during school. But it was so removed from my life and this modern era we live in that I never really understood the war. I’m not sure I can even say I do now, having only deeply visited one battle. But it lives in me as a visceral moment in time. It is so much more than something that happened back in the “olden days.” So much more than merely history.

Final Thought

One of the best things I heard during the tour at Carnton Plantation was when someone in my group asked the tour guide why he wasn’t dressed in period clothing (as you find at some tours such as when I visited Andrew Jackson’s Hermitage). His answer, “I wasn’t born a Confederate. I was born an American.”

That remains with me because, as I learned, there are some in the south who are deeply resentful and angry that the south lost that war. And it shows in the ugliest of ways. Soon, I’ll share the fourth and final installment about Middle Tennessee, I will share coming face to face with racism. It was difficult and heartbreaking.

Toby and I enjoyed your history tour and as usual I felt like I was on the tour with you. So many young lives gone. A lighthouse job … fun! You will be great. Love, Marie

I love taking readers on the tours with me!

We toured this area!!! Love history and this area doesn’t disappoint!! Glad you were able to tour (and help clean up a bit).

Mike is from Nashville!!

I was just a little too far away from Nashville to go up more than one day, but I’m thinking next time I’m back in the area I might focus on Nashville. Obviously a lot to do and see there. And once in a while it si nice to be in larger cities. When I get there, I’ll get all the “must see” places from Mike.